A new imperial force contending for world dominance

Around 570 AD, Muhammad was born to an aristocratic clan of the Quraysh tribe that controlled Mecca, in what is now modern Saudi Arabia. His name means “praiseworthy” in Arabic. His father died before he was born, and his mother died when he was six, leaving Muhammad in the care of a grandfather and, later, a paternal uncle. Another uncle trained him in archery and swordsmanship, and yet another uncle engaged him to lead trade caravans. When he was 25, a wealthy woman and distant relative named Khadija invited Muhammad to lead one of her caravans to Syria. She was so impressed with his honesty and integrity she proposed marriage to him. He agreed and remained faithful to her until she died.

As an adult, Muhammad began retreating to a mountain cave to pray. At the age of 40 he told Khadija that the angel Gabriel visited him and give him revelations from Allah. Tradition holds that he was so terrified at first he asked her to cover him with a blanket. She encouraged him to trust the revelations and three years later, in 613 AD, Muhammad began reciting the verses of the Quran publicly.

The central message of the Quranic revelations was that Allah is the One true God, and total submission to Allah’s instructions is the only correct way of life. The word Islam, in Arabic, means submission. From then on, Muhammad declared he was a prophet whose duty it was to recite verbatim what the angel told him. Quran, in Arabic, means “to recite.”[1] That Muhammad was illiterate is considered by Muslims as proof of the miraculous origin of the 6,348 verses contained in 114 chapters of the Quran called surah.

Tensions rose between Muhammad and other Meccans due to his rejection of multiple deities traditionally worshiped at Mecca. Some Meccans sought to kill him, which led to his famous flight from Mecca to Medina referred to as the Hijrah, in 622 AD. Hijrah means “severing ties of kinship.” Islam began counting years from this point on. Muhammad was 52 years old. (The year 2025 AD is 1446 in the Hijri calendar.)

In Medina, Muhammad built a gathering place for public prayers, which were conducted facing north toward Jerusalem, reflecting his belief that his revelations were from the same God of Israel. Within two years, tensions rose with local Jewish tribes near Medina who rejected his revelations, which led Muhammad’s forces to expel two tribes and kill an entire third Jewish tribe. This led to changing the direction of prayer in 624 AD toward Mecca, and released violent conflict with not only the Jews, but also other tribes who opposed Muhammad’s forces throughout the region.

In 630 AD, Muhammad’s forces conquered his place of birth, Mecca. Ten months later he began a military conquest of Arabia, personally leading his forces to attack what was then the southernmost part of Christian Byzantine Syria. Altogether, Muhammad initiated some 65 military campaigns. He died in 632, after suffering a debilitating headache.

Islam Goes Imperial

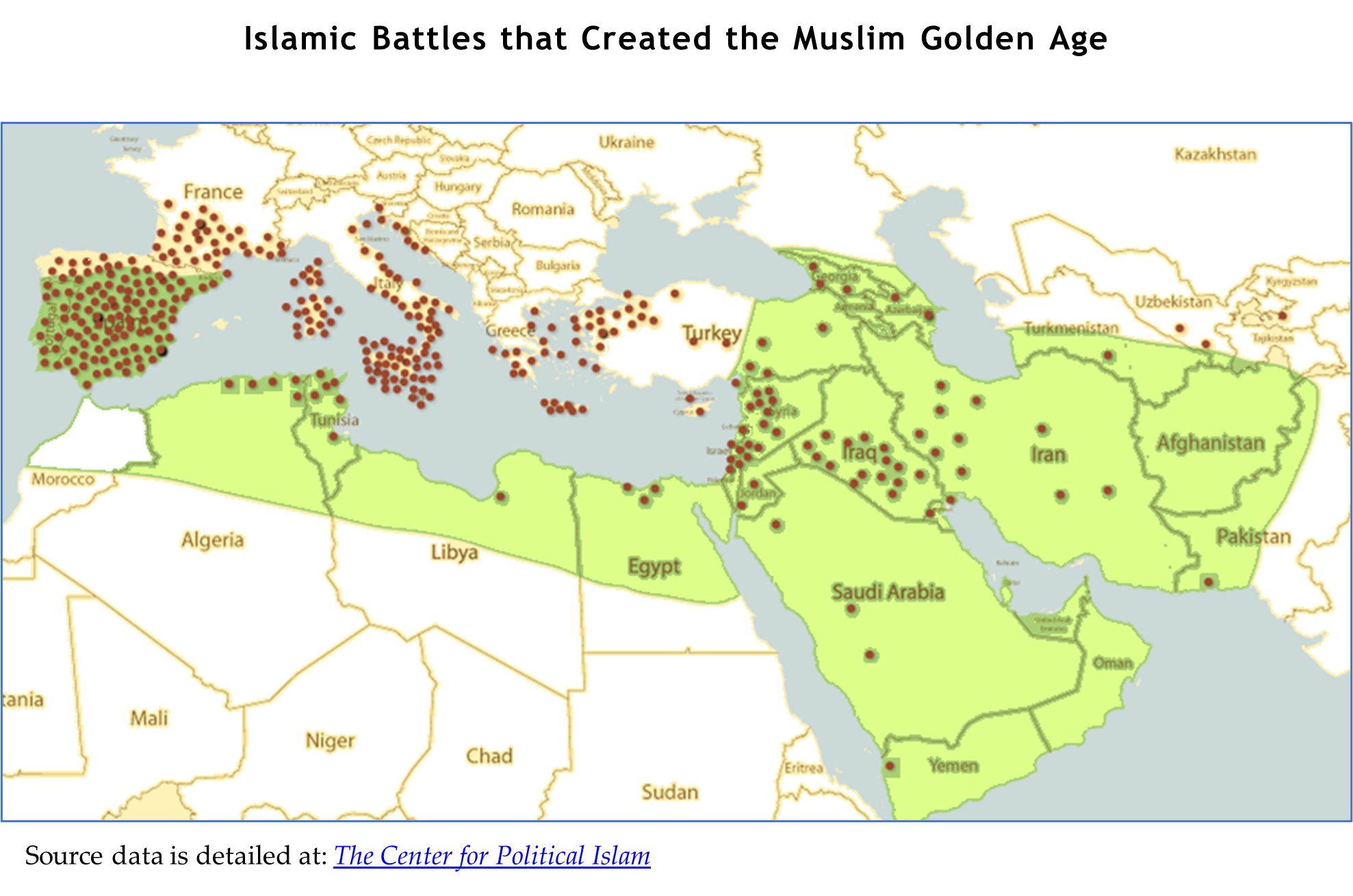

I’ll share more details about the Quran and Muhammad’s teachings in later briefs, but here I want to highlight that Islam emerged as an imperial force to be reckoned with following Muhammad’s conquest of the Arabian Peninsula. His Quranic revelations during this time set in motion a religious duty to conquer non-Muslims that proved more rapacious than anything Augustine’s Just War theory might have anticipated. (See map, above.)

Within only six years of Muhammad’s death, his successor caliph conquered Jerusalem (638 AD), the birthplace of Christianity. Within thirty years, the Muslim empire spanned three continents, including people living within the modern borders of over 28 countries. The second caliph pushed the empire into Spain and to the frontiers of India. Within a hundred years, Islam eclipsed the territorial expanse of the Roman Empire at its greatest. Later Muslim rulers would expand even further across the Sahara, south to Madagascar and as far east as modern Indonesia.

The Muslim blitzkrieg crippled the economy of the Eastern Roman Empire and left Byzantium incapable of supporting its far-flung outposts. Christianity’s ancient civilization was entirely at risk. Author Helena Schrader summarizes: “Throughout the four hundred years between the fall of Jerusalem in 638 and the First Crusade in 1095, Christendom had been fighting perpetually—and often desperately—for its very survival.”[2]

Islam’s Golden Age

It is common in the West to characterize Islam as an inherently peaceful and enlightened religion whose empire united much of the world in a Golden Age of cultural brilliance. In reality, Islam’s Golden Age mimicked the 200-year era of Pax Romana during the early Roman Empire, when Roman citizens enjoyed relative peace while Roman Emperors waged war on other nations around them. Previously, Alexander the Great had conquered the world during the Golden Age of Greek philosophy when Socrates , Plato and Aristotle lived. You could say one nation’s Golden Age was often other nations’ bane and enslavement.

In this context Islam is at least as much, or more, of a political ideology than it is a religion. Approximately half of Islam’s sacred texts speak about fighting non-Muslims, concluding: “Fight them until there is no more discord and the religion of Allah reigns absolute.”

The sayings of Muhammad carry as much weight as the Quran and add this in the prophet’s own words: “I have been directed to fight the Kafirs [non-Muslims] until every one of them admits ‘There is only one god and that is Allah.’” [3]

In short, non-Muslims lie outside of the religion of Islam yet form an integral target for Islamic rule. Islam scripturally justifies use of violence to subjugate non-Muslims, and operates as a totalitarian political system with respect to non-Muslims. This reality has been consistent throughout Islam’s history down to the present. (See Messiah Brief 14, The Jihad Spirit of Islam.)

Europe Responds to Islamic Aggression

In 800 AD, European civilization began a comeback against Islamic aggression when the Roman Pope crowned a Frankish leader, Charlemagne, “Holy Roman Emperor,” the first emperor in the West in over 300 years. [See text box below] He succeeded in uniting most of western and central Europe, and entered a peace treaty with the Eastern Roman Empire based in Constantinople.

Meanwhile, Seljuk Turkish Muslims arose from the steppes of central Asia to form a Turko-Persian Muslim empire (1000-1250 AD) that soon gained control over most of Byzantium’s eastern frontier. Approximately two-thirds of the ancient Christian world was soon ruled by Muslims, and Constantinople itself was at risk of conquest. In 1095, the Byzantine emperor wrote the Roman Pope asking for assistance. At a gathering of churchmen and knights in southern France, the Pope built on a grassroots movement called the “Peace of God” that had arisen a hundred years earlier. It was a populist response based loosely on Augustine’s Just War Theory, formed to defend Christians from marauding pagans and competing fiefdoms. The Pope reframed it as a religious duty to fight for the Peace of God to protect Byzantine Christendom from the Muslims. He also said the sins of anyone who joined the Crusade would be forgiven. In a rousing appeal, he proclaimed “God wills it!” which became the Crusaders’ battle cry.

The Crusades

After a bewildering series of missteps and diversions the First Crusade finally succeeded in returning Jerusalem to Christian control in 1099. Many saw this as proof God willed it. However,

Charlemagne and Millennial Fever

A little known factor in Charlemagne’s crowning was the choice of the year 800 AD. Scholars recognize this as a computation of the year 6000 Anno Mundi (AM, “Year of the World”), based primarily on genealogies in the biblical book of Genesis.

The Bible says 1000 earthly years equal one Godly day (Psalm 90:4, 2 Peter 3:8). So 800 AD = 6000 AM, or 6 days in God’s timing. This can be interpreted as leading up to a “seventh day” when Jesus would return and God’s Kingdom would reign on earth for another “day” equaling 1000 years (Revelation 20:1-4). This seventh day is viewed as a kind of “sabbath era” in God’s timing.

However, Jesus told his followers: ” Truly…you will not finish going through the cities of Israel before the Son of Man comes” (Matthew 10:23). When Jesus didn’t return as expected, it became an issue. By the third century AD, writers began interpreting Christ’s return as allegorical or delayed until certain scriptural conditions were met. Others sought to remove the Book of Revelation from the Bible because it mentions Christ’s return. Church leaders emphasized Jesus’ kingdom is “not of this world” and focused on serving the church in the present, including fighting just wars against barbarians and Muslims.

As for Charlemagne, 2 Thessalonians 2:7 says: “For the secret power of lawlessness is already at work; but the one who now holds it back will continue to do so till he is taken out of the way” (NIV). Pope Leo III viewed the new Holy Roman Emperor as the one who holds back lawlessness. But instead of relying on the Ano Mundi calendar, which would imply Jesus’ return was right around the corner, Charlemagne’s coronation was timed to the Anno Domine calendar which implied Christ’s return would come 200 years later, in 1,000 AD.

As 1,000 AD approached, millennial fever broke out across Europe, propelling many to make pilgrimages. It also helped inspire the “God’s Peace” movement in France, which motivated the Crusaders to set out to restore the Holy Land to Christendom. Some scholars see this as an expression of “French millennialism” a precursor to the French Revolution and modern secular expressions such as Marxism and socialism that promise a utopian future that never arrives.

Isaac Newton, an avid student of Biblical prophecy, wrote far more about the Bible than science. He concluded the crowning of Charlemagne in 800 AD was a milestone for counting down to Christ’s return. But based on Daniel’s prophetic timeline, Newton deduced Christ would not return until after 2060-70 CE. (For more, see Millennialism, by Richard Landes, in Encyclopedia Britannica.)

subsequent crusades met with mixed results and offshoot mini-crusades embarked on an assortment of local wars, even against competing Christian fiefdoms, as the mélange of Crusading forces exploited their belief they were fighting wherever they went because God willed it.

Scholars count the overall number of crusades in different ways, but some markers stand out. A Kurdish Muslim ruler Saladin regained control of Jerusalem for a time in 1187. The Third Crusade (1189–1192) aimed to recapture it but failed. Not until the Sixth Crusade was Jerusalem recaptured, in 1229.

Sectarian divisions among competing Muslim rulers raised hopes in the West for more success, but divisions also occurred among Crusader forces. Finally, the Holy Land was lost for good to Mamluk Muslims in1291.[4] Within eleven years the Mamluks expelled the last Crusaders from the entire region, bringing the major Crusades to an end.

Not long afterward Ottoman Muslim Turks emerged from Central Asia and migrated to the Turkish peninsula, which they conquered in 1517. Their victory established the Ottoman Empire which would become the longest lasting (but not geographically largest) Muslim Empire of all. The Ottomans reigned for 400 years until the end of World War I, and were formally replaced in Turkey by a secular ruler in 1922.

Fallout of the Holy Roman Empire

After the Crusades the Holy Roman Empire was mostly an empire in name only. Many wars were fought contending for its power. The Hundred Years war (1337-1453) saw five generations of English and French kings fight over the throne of France, interrupted for a time by the deadly Black Plague (1347–1351). Estimates of total dead from that war, including the plague, range from 2.3 to 3.5 million. Not long afterward the Thirty Years War (1619-1648), one of the most destructive wars in European history, produced as many as 8 million casualties. Napoleon finally ended the Holy Roman Empire in 1806.

Despite this turbulent history, the Holy Roman Empire entrenched the idea of the church and state working together to solidify, defend and expand Christianity. This worldview would be challenged when the protestant Reformation emerged in the early 1500s, propelled by the power of the movable type printing press. As kingdoms came under the influence of competing political and religious forces, boundary issues between church and state arose that would percolate for over 500 years. The American revolution, French revolution and Marxist revolutions would each weigh in differently on how to separate faith and politics. Church and state issues still turn up in American constitutional debates to the present day, as I’ll discuss later.

[1] It is widely held that Gabriel continued giving Muhammad revelations that form the entire Quran, but Gabriel is only mentioned by name (Jabril in Arabic) three times in the Quran. Some translators characterize Quranic references to Gabriel as not referring to an angel but to the Spirit of God. That’s interesting, given that the Quran decisively rejects the trinitarian revelation of the Bible. See: Is Gabriel (Jibril) An Angel? Other sources cite a range of Biblical and extra-Biblical sources that some scholars believe directly influenced Muhammad’s revelations. See: https://www.answering-islam.org/Gilchrist/Vol1/index.html.

[2] Helena Shrader, https://www.quora.com/What-were-the-biggest-atrocities-committed-during-the-Crusades-on-both-the-Christian-side-and-the-Muslim-side. Shrader details Muslim conquests that preceded the Crusades, and includes a detailed list of her sources.

[3] Muhammad’s quote is from Bukhari 4, 52, 196 Mohammed. “Political Islam, a Totalitarian Doctrine,” by Dr. Bill Warner, lists Muslim battles initiated against non-Muslims here: https://www.politicalislam.com/political-islam-totalitarian-doctrine/

[4] Mamluks were powerful enslaved soldiers who served Muslim caliphs, rather like loyal mercenaries of today.

Leave a Reply