The brooding empire that propelled global revolutions

The ancient quest for Russian identity birthed a violent empire and a rich literary tradition preoccupied with deep brooding about the “Russian Soul.” The writer Dostoevsky characterized it this way in A Writer’s Diary:

The most basic, most rudimentary spiritual need of the Russian people is the need for suffering, ever-present and unquenchable, everywhere and in everything.

Dostoevsky depicted Russian suffering with vivid realism and haunting images that evoked humanity’s universal struggle with evil and “demons of the soul.” He wrote from personal experience, having faced a firing squad as a young man for his role in a radical intellectual group. Miraculously, the tsar abruptly commuted his sentence and sent him to Siberia instead.

Dostoevsky depicted the painful travail of life in Imperial Russia and anticipated the crushing persecution that would one day emerge in the Soviet Union under Lenin and Stalin. But before all that the Russian Empire itself was born out of suffering that precipitated the third largest empire in history, behind only the far-flung British Empire and the fleeting realm of the Mongolian hordes.

Imperial Russia

Imperial Russia was headed by powerful autocrats and advanced by military conquests that ranged from the Baltic Sea in the west to the Pacific Ocean. At its height, Russia laid claim to Alaska, sustained outposts in Hawaii, and manned Fort Ross (“Rus”) in Sonoma, California!

The Russian Empire was officially inaugurated in 1721, under Peter the Great, when the Russian “Senate” (consisting of ten nobles and ten Russian Orthodox priests) conferred on him the title Emperor. The word meant the same thing as Tsar (“Caesar”), but was intended to position the new emperor on a more equal footing with rulers in Europe who saw Russia as a primitive backwater of a nation.

Peter the Great was enamored with the west and traveled widely in Europe in search of knowledge and connections that could help advance his ambition to transform feudal Russia. Ever the strong autocrat, he introduced European Enlightenment ideas and promoted science and industrialization back home. A major goal was to modernize his army for conquest.

To fund his military campaigns, Peter levied new taxes and introduced Western ecclesiastical influences to reduce the power of the feudal Russian Orthodox church. Among other things, he imposed his own authority over the church and invited more progressive Ukrainian and Belarusian clergy to fill church leadership positions at the expense of Russian priests.[1] Many parcels of land formerly owned by Russian monasteries came under state control, and over a million peasants became serfs of the state overnight. By the mid-1700s, the number of monks declined by half, and the majority of local churches were led by Ukrainians directly dependent on the Emperor.

The Brutality of Russian Emperors

Russia learned by experience to rely on brutal autocratic rule. In the 1500s, Ivan the Terrible set an example as the first Tsar. He earned his nickname from his fiery temper and was responsible for the deaths of some 60,000 people. In the early 1600s, Polish and Swedish forces invaded Russia during a time of famine and chaos. Over a million Russians died (one estimate says 5 million). The tsars learned the hard way that power had to be wielded mercilessly from a position of strength to protect Russia.

Peter the Great decided it was essential to conquer European nations that threatened Russia, including Sweden and the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. In 1709, Peter’s army repelled the Swedes, beginning a centuries-long pattern of Russian rule over eastern Europe. Peter also conquered regions to the south formerly ruled by Ottoman Turks. Much later, the Soviets would follow Peter’s model. Vladimir Putin even mentioned Peter the Great by name as a role model during his 2022 invasion of Ukraine.

Peter was notoriously brutal. He is said to have personally lopped off the heads of a group of prisoners between shots of vodka. He even oversaw the torture and death of his own son in order to assert the importance of state priorities over personal interests. His brutal example would carry over two centuries later to the Russian communist revolution.

There’s no definitive record of deaths under Peter’s reign, but accounts suggest the population of Russia declined by as many as 3 million.[2]

The Russian Pogroms

When Russia conquered territories in Eastern Europe and from the Turks (1772-1815), large Jewish populations became part of the Empire. Russia referred to these territories as the “Pale of Settlement.”[3] “Pale” refers to fence “posts,” meaning boundaries. Jews were held in contempt by the Russian Orthodox Church, and were confined to the Pale unless they converted to Christianity or became more economically useful.

By the late 1800s Jews began to suffer persecution throughout the Pale, particularly during Russian Pogroms. “Pogrom” means devastation perpetrated by violence. The pogroms erupted following the assassination of Czar Alexander II in 1881, for which Jews became the scapegoats.

In 1903-06, a second wave of pogroms broke out in 700 towns and villages mostly in Ukraine and Moldova, both part of Russia at the time. Records show at least 3,000 Jews died in Odessa alone, a number some historians consider conservative. Jewish property and businesses were destroyed. Reports circulated of people being thrown from windows, women raped, and murdered babies—bringing to mind Hamas’ holocaust in Israel in 2023. The New York Times reported that some of the attacks in Russiawere led by Orthodox priests and the Tzar’s secret police.

A third wave of pogroms occurred during 1917-1920, immediately following the Russian Communist Revolution. These pogroms were led by Ukrainian nationalists, Polish officials and the new “Workers’ and Peasants’ Red Army.” As many as 250,000 Jews were killed and 300,000 Jewish children orphaned!

Russian Antisemitism Goes Global

Jewish emigres weren’t the only export during the pogroms. Russians turned antisemitism into a viral global creed, shifting its tone in the late 19th century from a narrow focus on religious Judaism to depicting Jews broadly as people with innately defective moral qualities. One expert caricatured Russian attitudes toward Jews this way:

“The Jews killed Christ, the Jews do not want to accept the truth of Christianity, the Jews made money off the war, the Jews are profiteers, the Jews cheat you in business. The Jews have a certain phenotype: the Jew has a hook nose, the Jew is loud, the Jew talks with his hands.”[4]

Exhibit 1 for this stereotype were the infamous Protocols of the Elders of Zion, the most widely circulated antisemitic rant ever produced that still has legs today. It appeared in book form in 1905, in 24 chapters called “protocols,” describing alleged minutes of fictitious meetings of Jewish conspirators planning to rule the world by manipulating economies, controlling media, and provoking religious conflict. The Protocols soon found their way to Europe, America and other world centers, including an early Arabic edition.

In 1921, the London Times exposed the Protocols as a fraud at the same time that Henry Ford was publishing an adaptation called “The International Jew” in Ford’s newspaper The Dearborn Independent. He was inspired by Darwin’s theory that evolution favored survival of the fittest races. Ford deemed the Jews unfit. Hitler praised Ford’s gesture, hoping to garnish his own credentials by highlighting a like-minded American.

The Seething Cauldron in the 20th Century

Russia’s cauldron of suffering soon spilled over into the “new Russia” following the 1917 Revolution that divided Russia into violently opposed communist and anti-communist factions. It is believed that at least two million people died during the Revolution, about 7% of Russia’s total population. Another 7% emigrated. Famines in the 1920s and 30s added to the loss of life as did state organized persecutions of people seen as threats to the communist Soviet state under Vladimir Lenin and his successor, Joseph Stalin. Echoing Robespierre, the communists took the position that if you weren’t actively for the revolution, you were against it.

The conundrum of the Russian Soul was in full display as the communists denounced antisemitism while at the same time endeavoring to destroy Jewish life. Lenin criticized antisemitism as an “attempt to divert the hatred of the workers and peasants from the exploiters toward the Jews.”[5] For Lenin, the real exploiters were the capitalists. When someone joined Lenin’s Bolshevik Party, they were deemed to be exchanging ethnic struggle for class struggle, religious faith for atheism, and patriotic chauvinism for “internationalism.”

While re-education programs condemning antisemitism were being implemented in the Red Army and places of work, Jews were at the same time undergoing severe persecution. The communists seized their property and synagogues, and rabbis were forced to resign under threat of violence. The irony went further because some ranking Bolshevik party members were Jewish, which the communists hid to prevent accusations that communism was under Jewish influence—which risked evoking unwanted shades of the Protocols of Zion.[6]

Purging the Party to Concentrate Power

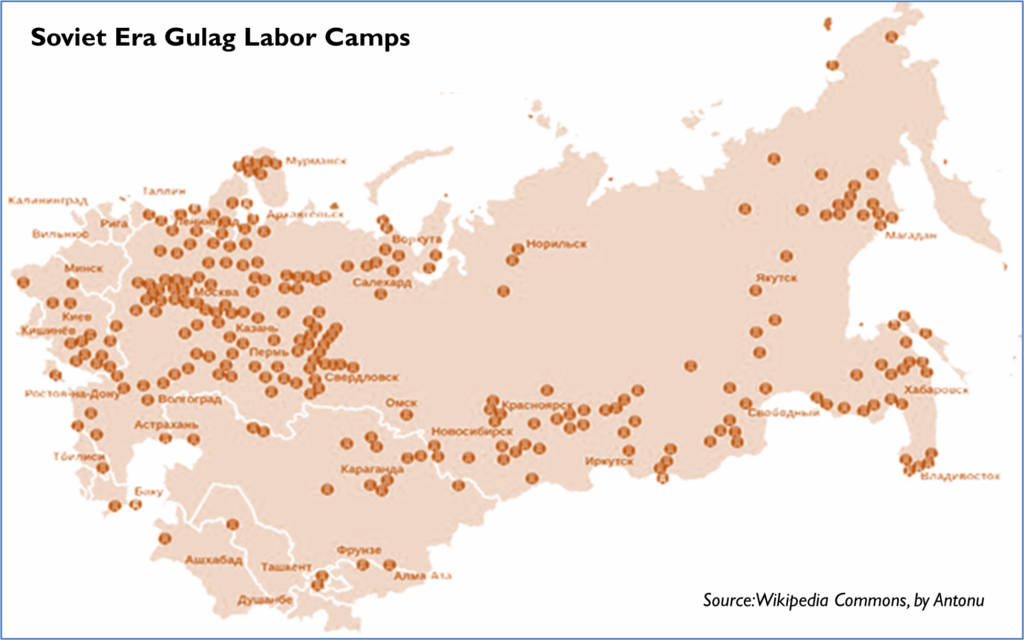

The elite Bolsheviks who led the Bolshevik Revolution comprised a small centralized group who controlled the Communist Party, and thus the entire new Soviet Socialist Republic. They believed in “revolution from above” and sought little input from the rank and file. The Bolsheviks ruthlessly suppressed political enemies, real or perceived, and relied on party purges to remove people who displayed less than total dedication to the party’s leadership. Here again were echoes of the Franch Revolution. The purges relied on fear, secret police, and forced labor camps, which ultimately produced a death toll far greater than the earlier tsarist pogroms. Under Lenin, at least 84 labor camps were established and some 200,000 people were purged.

Stalin too had a complex history regarding Jews. Early in his career, he wrote a paper with Lenin’s approval denying that Jews had any true national identity under capitalism and asserting they also wouldn’t under communism. In the first Soviet government (1917-23), Stalin served as “commissar of nationalities” officially responsible for supporting Jewish affairs for “stateless people.”

When Stalin succeeded Lenin as General Secretary of the Communist Party in 1924, he maintained the state’s official antisemitic stance for ten years, while also implementing antisemitic policies couched in language opposed to “Zionism.”[7] The Jewish Zionist movement to resettle Palestine was seen as an expression of Western capitalist/colonial exploitation that ran counter to communism. This perspective would be advanced later by Israel’s Arab enemies, as I explain more in the next two briefs.

During this time the Soviets formally enacted state atheism, becoming the first nation in the world to make separation of church and state a formalized constitutional principle.[8] All religious organizations were deprived of property rights, as well as rights as legal entities. This laid the foundation for atheist re-education and persecution of churches. In 1925 the League of Militant Atheists was formed to step up persecution against churches, Jewish temples, and mosques by killing and imprisoning many religious leaders. Less than 15 years later, only 500 out of 50,000 churches remained open in the Soviet Union.[9]

The Infamous Soviet Gulag

Gulag means “camp” in Russian and refers specifically to forced labor camps to which the Soviets sent millions of Russians and others who were seen as opposing them. Under Stalin, some 30,000 camps were set up (see map, next page), and 18 million people were detained from the 1920s until 1953.[10] The camps housed from 2,000 to 10,000 prisoners under extremely inhumane conditions involving long work hours and harsh weather. Many died of exhaustion, starvation and disease. One estimate published in Russian schoolbooks in the 1990s said 20 million Soviet and East European citizens died in Communist labor camps, and 15 million were killed in mass executions. They included political dissidents, Christians, Jews, and others.[11] In 1995 a Russian State commission claimed that at least 200,000 Russian Orthodox priests, monks, and nuns were killed.

The Gulag camps epitomized the suffering of the Russian soul Dostoyevsky once foresaw. Author Alexandr Solzhenitsyn would document them in powerful writings which earned him a Nobel Prize in 1970. He spent eight years in a gulag (1945-1953) for opposition to Soviet oppression, followed by three years of exile in Kazakhstan. His first novel, One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich (1962), fictionalized those experiences.

Solzhenitsyn’s most famous work, The Gulag Archipelago, a non-fiction series, sold over thirty million copies in thirty-five languages. In it, he identified the motivation behind the camps:

Ideology – that is what gives evildoing its long-sought justification and gives the evildoer the necessary steadfastness and determination. That is the social theory which helps to make his acts seem good instead of bad in his own and others’ eyes…. That was how the agents of the Inquisition fortified their wills: by invoking Christianity; the conquerors of foreign lands, by extolling the grandeur of their Motherland; the colonizers, by civilization; the Nazis, by race; and the Jacobins…by equality, brotherhood, and the happiness of future generations… Without evildoers there would have been no Archipelago.”[12]

Solzhenitsyn’s research concluded that more people died than the official Soviet records showed. He totaled 66 million dead under Stalin, mostly Christians, from 1919 to 1957. The “death camps” are noteworthy because more people died after the Russian Revolution and rise of Stalinism than during the Revolution itself. This is a vivid picture of the power of a deadly ideology used to turn Russian souls against themselves under the forceful will of a very small minority, just as Solzhenitsyn wrote.

Suffering As Religion

Summarizing what we’ve seen in this chapter, the Russian Empire that began under Peter the Great collapsed after two centuries to irrepressible forces of modernism. In its wake, the Bolshevik Revolution turned Russia’s paranoid patriotic power inward against Russia’s own people as it sought to completely eradicate the vestigial grip of feudal Russia. In its place the communists imposed atheistic Marxist ideology that rejected all religions. In place of the Pale of Settlement that once isolated Jews, the Soviets developed a pall of death camps that darkened the lives of all who were so much as suspected of being opposed to Soviet ideology.

Under the guise of anti-Zionism and a communist mandate to export wars of liberation to other nations, the Soviets succeeded in transforming Marxist ideology into a religiously fervent international crusade of violent revolutions. A global trail of blood and devastation would become the hallmark of their fervor wherever communist guerillas embraced their cause.

[1] The Ukrainian Orthodox Church predates the Russian Orthodox church by centuries, having been formed by Jesus’s apostle Andrew, who traveled in the region and foretold a great church would be established in Kiev. In our time, the Russian Orthodox Church backed Putin’s invasion of Ukraine in opposition to the Ukrainian Orthodox Church, a tension traceable to the two ancient churches from the time of Peter the Great.

[2] See http://necrometrics.com/pre1700a.htm#Mongol. See estimates numbered 24, 29, 31, 36, and 42.

[3] The Pale included modern Poland, Ukraine, Belarus, Moldova, Lithuania and Crimea.

[4] “Ford’s Antisemitism,” Professor Hasia Diner interview. See https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/henryford-antisemitism/.

[5] March 1919 speech quoted in Wikipedia under “Antisemitism in the Soviet Union.”

[6] See https://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/was-lenin-jewish/.

[7] See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Antisemitism_in_the_Soviet_Union.

[8] Decree on Separation of Church from State and School from Church, January 1918. Note that separation of Church and State is not formalized in the U.S. Constitution, but is based for judicial purposes on legal interpretation.

[9] https://www.loc.gov/exhibits/archives/anti.html.This tally found in the U.S. Library of Congress dates from 1939.

[10] https://www.wilsoncenter.org/event/death-and-redemption-the-gulag-and-the-shaping-soviet-society

[11] The London Tablet by Jonathen Luxmoore, published in Chesterton Review, Feb/May 1999.

[12] Aleksandr I. Solzhenitsyn (1973). Chapter “4”. The Gulag Archipelago (1st ed.). Harper & Row. p. 173. (Quoted in Wikipedia.)

Leave a Reply